Please note: this review provides substancial details and quotes from the book that has just been published.

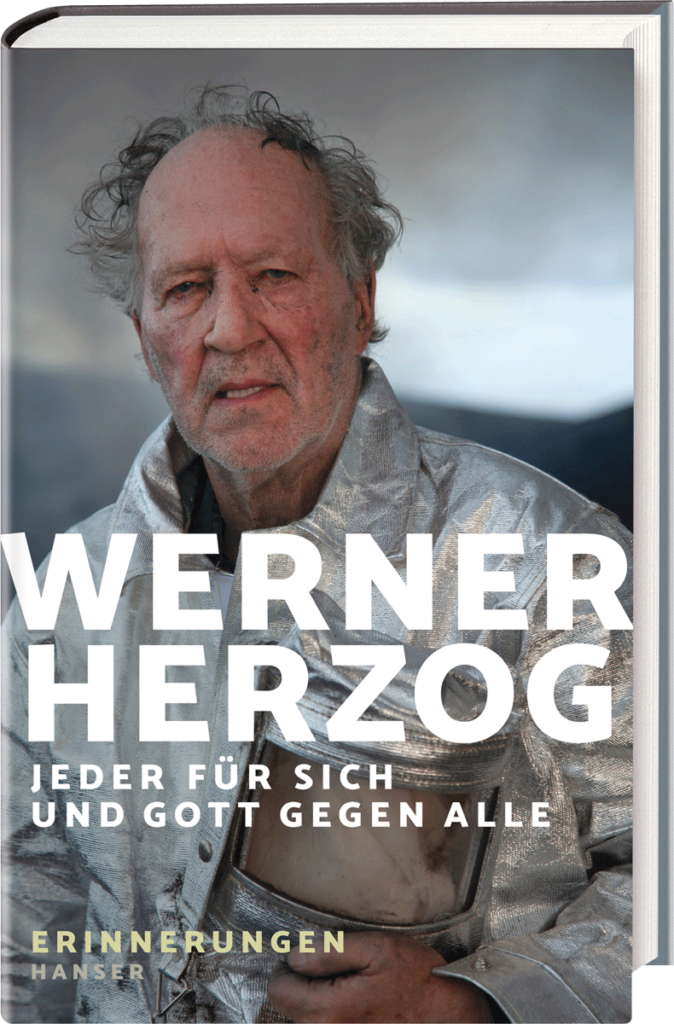

Like Edgar Reitz, Werner Herzog also used the time of restrictions on public life to write his autobiography. The book entitled Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle – Erinnerungen (Each for Himself and God Against All – Memories) will be released today (22 August 2022) by the Carl Hanser Verlag as a printed book and e-book and by tacheles!/ROOF Music as an unabridged audio book read by Herzog himself.

How can a person of such irrepressible willpower thrive that he is able to have a 340-ton steamship moved over a hilltop in the Peruvian jungle? Being a person of such peculiarity and authenticity that he seems unmistakable and formative; being a person of such worldliness that he uses the entire globe, from Patagonia to Antarctica, Africa, and the jungles of South America to the Siberian taiga as his home and studio? Or being a person who does not shy away from any challenge, makes the unthinkable come true even against all odds and thus leaves lasting traces, conveys food for thought and new perspectives, and opens gates to unknown worlds that one’s own eye could never have seen?

Of course, we are talking about Werner Herzog, who in his generation, the generation of the WWII children, is certainly unique, and unparalleled; any attempt to copy Herzog, or to imitate him, would be doomed to failure on all levels. Werner Herzog, who is turning 80 these days, has written his autobiography, a „literary event“ as the publisher rightly announces, and he thus gives us profound insights into his rich life. He helps us to understand what shaped him and how a spirit of such energy, creativity, intelligence and vastness could grow – especially by taking us on an intensive journey into his childhood and youth in Sachrang, Wüstenrot and Munich, which on one hand is characterized by massive deprivations (e.g. no shoes in summer, no underwear in the months without „r“, Outhouse, hunger and rarely electricity), and on the other hand by unusual experiences and encounters, be it with the village natives in Sachrang – the Maar and the seal Hans – or Klaus Kinski, who lived for a while in Munich’s Elisabethstraße in the same guesthouse in which Herzog had been accommodated with his mother and two brothers in a small room.

It is pointless to go into biographical details in this review or to give in-depth examples, as much is already known and Werner Herzog’s life is too rich in events; each of which would be worth retelling in its own right. Nothing he can tell us is ordinary, just as he himself is not an ordinary person. The title of his memoirs, „Everyone for himself and God against all“, is his second attempt after the Kaspar Hauser film (1974) to establish his variation of the old proverb „Everyone for himself, God for us all!“ and to confer the public perception. Even if Herzog does not explain directly why it is so important to him, from his descriptions it can be guessed that he alludes to the courage and energy of his own self, to the basic trust in life and one’s own course, which becomes feasible exactly when these three things are given, and hesitation and doubt do not determine one’s own thoughts and actions. It is strange to him to make his happiness depend on others, not even on God.

In trust, an outwardly perceived risk becomes an inviting challenge. Without this trust and Herzog’s incorruptible perseverance, there would not be Aguirre, where suddenly all the exposed negative material had disappeared, or Fitzcarraldo, where after about half of the shooting time, lead actor Jason Robards left the scene and all the work had to be started all over again.1

Economic concerns or even limits did not stop him from following his dreams. To finance his films, as a student he worked as a spot welder on night shifts, served in Crete as a fisherman, as an arena clown for the bullfight organizer Charridas, and smuggled consumer electronics in Mexico, trusting completely in the economic talent of his half-brother and producer Lucki Stipetić. Otherwise, his endeavors would have ended with the discontinuation of filming, and “I did not want to live as a man without dreams.”2

Even „real disasters“, bad misfortunes, serious physical injuries or illnesses did not stop him from going his way; his recounting especially in the chapter „Dance on the Rope“ makes you shake your head and sometimes smile, sometimes shudder. When he joined Fitzcarraldo one day „alone in a crowd of people he thought who had given up on me and doubted my capacity for accountability,“ he was not deterred. „My diary records, which became almost indecipherable and microscopic in my ever-shrinking handwriting, were then suspended during my stay in the jungle for almost a whole year, the year of temptation. But I was always ready to face everything straight on, whatever work and life would throw at me.“3

And finally, there is another characteristic of Werner Herzog that made him who he is: his irrepressible, unbiased, and boundless curiosity paired with a profound technical understanding, high intelligence, a childlike thirst for research, and an unwavering unclouded self-confidence.

I was aware that – out of an almost complete ignorance of cinema – I had to invent cinema myself in my own way.4

Herzog’s narrative style is naturally consistent, in that he does not build the book chronologically along his films but draws on aspects of his work whenever it comes to make the reader understand how formative creative ideas were created and pursued, new connections were made or critical situations were mastered, thus opening doors for new paths. Again and again, people play a role here, whether as historical or character role models or as supporters or helpers who were willing to get involved in Herzog’s dreams. Without companions like Lucki Stipetić or his production manager Walter Saxer and his cameramen Thomas Mauch, Jörg Schmitt-Reitwein and Peter Zeitlinger, he would never have been able to unfold his irrepressible urge in search of ecstatic truth in this form. But it becomes just as clear how, as the nucleus of staging the unthinkable, he was never too shy to stand up for his dreams or for very substantial things such as the search for food for the entire staff of Aguirre at night in the middle of the jungle and not to shy away from massive loss of comfort, or even highly existential deprivation. Here, too, he shows a sense of responsibility, energy, courage and at the same time an incorruptible reliability. He was always the staple that held together the irrepressible complexity of his projects on all levels, and always proceeded in an exemplary, dedicated manner completely free of airs.

„Self-reflection, any circling around one’s own navel, is deeply uncomfortable for me,“ Herzog reveals, and his self-description, which he describes as „Slow reading, long sleep,“ is correspondingly rigid and emotionless. But on the other hand, immediately after talking about his friends or his wives, enthusiasm and warmth are palpable. He gives a particularly moving description of his relationship with the British author Bruce Chatwin, who provided the template for Cobra Verde, which Herzog finally presented to him in stages on his deathbed. The two were deeply connected by their shared love of traveling on foot, and Herzog eventually inherited Chatwin’s backpack, which accompanied him to more than just Cerro Torre. „Bruce‘ and my way of walking forced us to seek refuge, to get in touch with people, because our vulnerability required it.“5

And so it becomes clear how much Herzog’s monumental wanderings from Munich to Paris, along the German border and across the Alscharte, all border experiences „in moments that had existential importance for me“6, gave him memorable experiences and strength.

Again, and again (…) the meaning of the world is derived from the smallest materials, otherwise never observed. This is the stuff from which the world arises anew. At the end of the day, the one who left could no longer count the riches of a single day. When walking, there is nothing between the lines, everything takes place in the most immediate and ruthless present tense.7

He attributes a similar contemplative effect to the opera: „Working with music for a limited period of time, breathing music, transforming a world into music always brought me completely to my own center.“8 Between 1985 and 2015 he staged 26 operas on four continents, mainly in Italy.9

The collaboration with Edgar Reitz, one of the first of Herzog’s many works as an actor, is also mentioned; between the Kübelkind episode „Der Hurenmörder“ („Roles of madmen or villains were written on my body from then on“) and his embodiment of Alexander von Humboldt in Die andere Heimat have come full circle. Edgar Reitz, who at the time headed the Institute for Film Design at the HfG Ulm with Alexander Kluge, is to be thanked for his constant comradely support and lasting contacts, e.g., with editor Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus. Reitz’s personal invitation to the HfG, however, he rejected, being the consistent autodidact: „I never believed in universities“.10

For Werner Herzog, the greatest of all the actors he has ever worked with is Bruno S. , his Kaspar Hauser and Stroszek: „His face and his haunting language gave him an unconditional dignity. He was like an outcast who staggers confused towards you from a long, bad night into an even worse, garish day. He had a depth, tragedy and truthfulness that I have never seen on a screen otherwise.“11 Where Herzog formulates in enthusiasm and love, his words become particularly poetic.

The book ends in mid-sentence after 335 pages as part of a philosophical discussion of „The End of Pictures.“ Even if Herzog can offer a plausible explanation for this in the preface, this decision only testifies once again to what essentially defines him: his level, his independence, his trust, and his loyalty to himself.

The book is a real recommendation, not only for cineastes. Written in a fluid and straightforward yet very own way, unmistakably Werner Herzog. I’m especially looking forward to the audiobook version he reads himself. Thank you very much, dear Werner Herzog, for this worthwhile reading, entertaining and stimulating, but above all deeply impressive insights into your life.

© Thomas Hönemann, www.heimat123.de, August 22nd, 2022

Werner Herzog: Every man for himself and God against all. Memoirs

Editions:

Hardcover: Carl Hanser Verlag (Munich), 353 pages, ISBN 978-3-44627-399-3, €28.

e-book, Carl Hanser Verlag (Munich), ISBN 978-3-446-27561-4, 20.99 €

Audiobook: unabridged author reading on two mp3 CDs, tacheles!/ROOF Music, ISBN 978-3-86484-775-2, published on 31.8.2022 (digitally already on 22.8.), 26 €

heimat123.de recommends buch7.de, the social bookstore.

A reading sample can be found here, an audio sample here.

On the Hanser Verlag site you can also find dates of book presentations with Werner Herzog. Among them, the (belated) birthday party and book presentation for and with Werner Herzog deserves special mention. Musical accompaniment Ernst Reijseger, Mola Sylla and Harmen Fraanje, and „Cuncordu e Tenore de Orosei“ on October 30 at the Munich Schauspielhaus.

Publisher’s announcement text:

Werner Herzog’s long-awaited memoir recounts a life of the century that wouldn’t even fit into one of his own famous films. A perpetually hungry boy, fleeing with his mother from bombed Munich to a bitterly poor nest in the Alps. A youth who hitchhikes all alone and soon finds himself in the furthest reaches of Egypt, delirious with fever, waiting for death. A lover, an enthusiast, a driven man: a man who quietly talks to the raging Klaus Kinski in the middle of the jungle, a man who sits weeping for his friend Bruce Chatwin at his deathbed. Desolate and gentle, full of lust for life and amazement at our world, this book is a literary event.12

Translation of the original german version of this review with very kind and effective support of www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Images

- Cover © Carl Hanser Verlag

- Buchrücken (Beitragsbild) © Thomas Hönemann

Annotations

Fußnoten- Mick Jagger was also cancelled due to the upcoming world tour of the Rolling Stones; Herzog refrained from recasting and wrote the role from the script, because Jagger filled the role of the dimwitted Wilbur „so strange, so unique“ (p. 164) with life.[↩]

- p. 197 [↩]

- p. 200 [↩]

- p. 130 [↩]

- p. 229 [↩]

- p. 241 [↩]

- p. 243 [↩]

- p. 312 [↩]

- cf. p. 346f. [↩]

- cf. p. 293 [↩]

- p. 306 [↩]

- https://www.hanser-literaturverlage.de/buch/jeder-fuer-sich-und-gott-gegen-alle/978-3-446-27399-3/ [↩]