This text is a tranlation of the german original from Sept. 13th, 2022

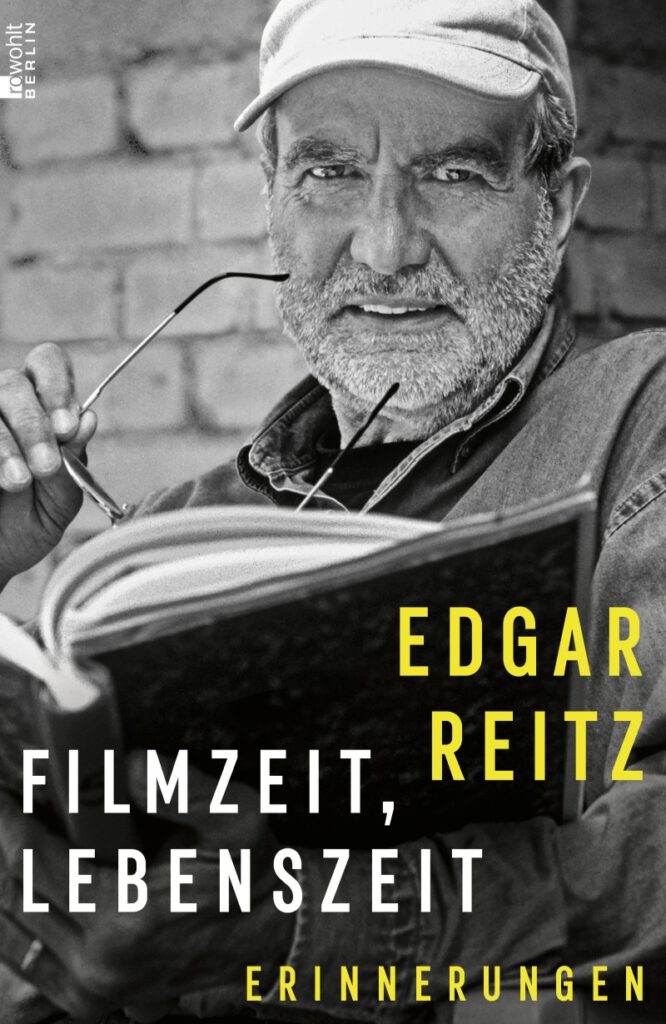

On Sept. 13th, 2022, with the title Filmzeit, Lebenszeit. Erinnerungen Edgar Reitz’s memoirs have been published. The book is avaiable as a printed hardcover edition under ISBN 978-3-7371-0159-2 (30 €) and as an e-book (ISBN 978-3-644-01417-6, 24.99 €) by Rowohlt Verlag Berlin.

The very personal, touching words in which Edgar Reitz introduces the early morning impulse that made him start writing his autobiography open up an intimate space for the reader. It becomes palpable that this is not about omitting, glossing over or transfiguring – especially since Edgar Reitz is no stranger to anything than self-promotion.1 Quite the opposite: for him, narration is now a “remedy against fear. For “in narration we bring our memories to safety. “2

The important film themes, these are not the themes one searches for, nor are they the themes that one sucks out of one’s fingers, it is the life that one lives oneself.

… Edgar Reitz spoke into the microphone of Bavarian television in the euphoria of the world premiere of Heimat at the Munich Film Festival on July 1st, 1984.3 He does not regard “film time” and “life time” as additive, mutually isolated spheres in the sense of privacy and profession, but rather shows at many points how much his life represents a sometimes intense fusion of these two. Not “art or life,” as he titled the last episode of Die Zweite Heimat, but art as a place of refuge from inner tearing: in art, “the whole body becomes the self.” “This is an enormous step into the freedom of the body “4 and thus into life.

Especially when Edgar Reitz tells us about his childhood and youth, many things seem familiar to us and the corresponding film scenes or characters inevitably appear on our inner eye.5 We know all this in poetic images – and yet we do not know it, because it is now embedded here, completely different and real life of a boy who was twelve years old at the end of twelve years of National Socialism and war, who was often (sometimes life-threateningly) ill in his childhood and youth and spent long periods in lonely sickbeds,6 who suffered privations and hardships, suffered from fears and nightmares, learned to fly in lucid dreams, and the more he was drawn to art the less he felt understood, until he finally broke with his family: “All the fibers of my soul wanted to break free.”7 “Don’t turn around!” his German teacher and patron Karl Windhäuser called after him.8 “Vom Ausreißen der Wurzeln” (uprooting the roots) is accordingly the title of the first part of the book – a process that he in part lets the character of Hermann Simon experience in a completely identical way, and thus makes it all the more vividly tangible for us.9

As is well known, Edgar Reitz heeded Windhäuser’s appeal, which was based on his Abitur speech (in which he drew on the legend of Orpheus leading Euridice across the Styx), only for a limited time. As early as 1972, he returned to Hunsrück for Die Reise nach Wien in order to fictitiously continue an episode from his mother’s life. In this context, he recalls a touching experience with Romy Schneider, whom he tried to win over for one of the leading roles, but who could not overcome the obstacle of an equal female role next to her. The final “turning around” took place at the end of the 1970s with the preparatory work for Heimat and opened a phase that Reitz describes elsewhere with the wink that “you go to a Hunsrück village and turn over every stone for 30 to 40 years and think that the world is there “.10

In his narration, Edgar Reitz repeatedly reflects on memories. This is especially the case when he talks about his first time in the “parallel world” of Munich and often has to admit, that his memories are so overlaid by the images of Die Zweite Heimat that he is no longer able to distinguish reality from fiction – his first wife Gertrud, as he reports in an interview with Der Spiegel, feels the same way about their wedding at the time.

With his autobiography, Edgar Reitz also succeeds in providing a convincing answer to the question (which, in my opinion, has so far only been answered in fragments) of how the Hunsrück war child and watchmaker’s son was able to become one of the greatest filmmakers of our time – less on the basis of the presentation of the mostly already known encounters and stations per se, but rather of the transitions and connections as well as the impulses and encompassing networks that shaped the phases of his life. Despite the particularity of his vita, he gives himself modestly and completely free of pathos; instead, he expresses deep gratitude several times in an honest and humble way. His story is one of serendipity and encounters (Windhäuser, Kutscher, Cocteau, Arnold (Arri), G’schrey, Zielke, Riedl, the Bayer Group, Mauch, Mainka, Handwerk, von Mengershausen, Eichinger, Roll, … ), which, however, would not have happened this way if he had not been open to all that life gave him, and had not at the same time brought with him a tremendous technical and aesthetic talent as well as an extremely alert mind, with which he could offensively and courageously convince potential supporters again and again and strike new paths – in the sense of art, and occasionally also against all the rules of reason. He himself sometimes expressed surprise at his own courage and determination, as well as at his ability to multitask “out of an almost manic drive for action. “11

For lovers of Edgar Reitz’s work, interesting, hitherto rather unknown details of his life and work keep revealing themselves. He also describes in detail little-discussed projects such as the lessons on film at the Luisengymnasium in Munich, from which the film Filmstunde emerged. Thus, the book becomes an enlightening and entertaining treasure trove in factual terms as well.

Particularly impressive and at the same time a very important aspect of his development is the episode on Willy Zielke, for whom Reitz worked as an assistant at the Munich GBF (Gesellschaft für Bildende Filme) in the late 1950s. Due to the reinterpretation in Heimat and Die zweite Heimat, where a certain Mr. Zielke emerges as a conservative cinematographic disciplinarian who, above all, is not open to anything new, this figure appeared – again a place where the distinction between fiction and reality is advised – in a different light. Zielke, who as a cameraman had worked significantly on Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia films and paid dearly for this because of her need for recognition,12 was instead a technically pedantic but very experimental and creatively, extremely innovative cameraman, to whom Reitz devotes an entire chapter under the simple heading “Zielke,” at the end of which he declares him to be his “real master”.13

Even in the factual fullness and stringency of his narratives, Edgar Reitz succeeds again and again in describing his emotions in a wonderfully straightforward and authentic way, thus making what he experienced comprehensible in depth. With this book, he opens up a new dimension of self-revelation by also reporting on his love and married life, often with loving enthusiasm and a great deal of empathy, especially for his former partners. Likewise, he does not omit personal crisis, whether of a professional or private nature, but also repeatedly explains how he was able to pick himself up again and motivate himself to continue, even after low blows such as the slating of the Schneider von Ulm or the day on which two women separated from him. He also takes a touching farewell to dear companions such as Alf Brustellin, Franz Bauer and Gernot Roll. And so the book is – in the truest sense – characterized by pure humanity, which is also evident in the fact that Reitz avoids judging and comparing. He has found his peace.

In many places of the book his’ great confidence in life and an unerring optimism, combined with an exemplary vitality, as well as a highly sensitive perception and bodily sensibility together with a deep understanding of the human soul become clear. He affirms his belief in fate and that there are no coincidences. Just when I was thinking whether I could therefore (without provoking his contradiction and unsure whether we understand the term in the same way) call him a spiritual person, he himself provides an indirect answer by telling about a “spiritual experience “14. One senses his open mind whenever Edgar Reitz gets into philosophizing about life, for example when he pursues the question “How the I comes into being” at the beginning of Part 2, or reflects “On Forgetting” in the concluding chapter in memory of Hinderk M. Emrich.

Actually, as Edgar Reitz confesses in an interview with Der Spiegel, he didn’t want any images in this book (“I fought very hard against it (…). The pictures should be created in the mind.”), but in the end it turned out to be 3 panel parts on 24 pages. Pictures that show by far not only himself, although the portraits of Jim Rakete and Herlinde Koelbl may not be missing, of course. The picture that appealed to me most was taken in 2014 at the small film festival in Pessac, France, where he and Salome presented Die andere Heimat (engl. title Home from Home) and met Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta. The “old New German Cinema as lifelong friendship “15 and history of ever closing circles. And a historical picture of 1977 with him, Alexander Kluge and Rainer Werner Fassbinder in the context of the omnibus film Deutschland im Herbst (germany in Autumn).

A wonderful book by a very special person whose multifaceted life absolutely belongs to be told. The life experiences of Edgar Reitz allow us to dive into the political-social history and even more the film history of his time at the same time as his personal journey. A time characterized in particular by radical social and political upheavals (“One breathed revolutionary dreams virtually with the air. “16 ) and by increasingly rapid technical and aesthetic developments, especially in his profession, cinematography; Reitz had to reinvent himself again and again under the changing circumstances. In this respect, the book is also a (film) historical time document of a development and a life that can never again be lived in this way due to the now completely changed framework conditions. Something that unites him with Werner Herzog, almost 10 years younger, who also published his autobiography (see review in English) a few weeks ago.

It may make us pensive when Edgar Reitz, the visionary of cinema and cinematic art, repeatedly hints at an end-time mood.17 Regarding the current social and political developments, there is nothing seriously to be said against this. But isn’t every end merely making way for something new? And isn’t he himself a role model in terms of a great and unprejudiced openness to change? He was, for example, one of the first German filmmakers to embrace digital technology. Even if his documentary Die Nacht der Regisseure (The Night of the Directors) may seem technically outdated from today’s perspective, for the time it was made, 25 years ago, he was highly innovative with his idea of gathering the directors digitally (instead of in the flesh, which would have been impossible from an organizational point of view) in a cinema hall, along with its implementation. At the same time, he has always remained suspicious of digital technology; experiences such as the disappearance of all the footage from the first day of shooting Die andere Heimat in digital nirvana have strengthened him too much in this attitude.

Edgar Reitz describes the premieres and screenings of Die Zweite Heimat as “the happiest and most moving moments in [his] entire life.”18 A few days ago, Die Zweite Heimat experienced a rebirth in Munich, 30 years after its premiere at the Prinzregententheater, in the new guise of a digitally restored version. In this context, Edgar Reitz presented his memoirs for the first time.

The memories are safe. Fear may give way.

Thank you for sharing all this with us.

Thomas Hönemann, www.heimat123.de, Sept. 13th, 2022

Translation with kind support of deepl.com and Rowan Charlton

Many thanks to Rowohlt-Verlag Berlin for providing a review copy at an early stage.

Dates

Edgar Reitz will present his memoirs in person at various events, for example in the festive program of the Literaturhaus München as part of the Literaturfest München and at the Frankfurt Book Fair on Oct. 21; this event will be broadcast live by Hessischer Rundfunk starting at 8 p.m.

Further dates of readings and book launches can be found here.

On the occasion of the publication of the autobiography, Saarländischer Rundfunk and Südwestfunk (in the person of Sabine Mahr, who has been reporting on Reitz since the 1970s), among others, have spoken with Edgar Reitz. A very detailed interview has already appeared in Spiegel last Saturday (10.9.).

Announcement text of the publisher

Edgar Reitz co-founded the German auteur film, wrote film history with his Heimat-trilogy. Just as he impressively combined personal experience with the passage of time there, he does it here as well – in his autobiography. Reitz tells of his childhood in the 1930s, his youth during the war, the post-war period, the young man who is drawn to faraway places, his years as a student in Munich, where a new world of culture opens up to him, and finally of the art of film: together with the signatories of the Oberhausen Manifesto, he spreads the slogan “Papa’s cinema is dead! “He meets literary figures such as Günter Eich, international film greats such as Romy Schneider, Bernardo Bertolucci and Luis Buñuel, works with actors and actresses such as Hannelore Elsner and Mario Adorf, directors such as Alexander Kluge and Werner Herzog.

Reitz is a great chronicler of German longing and history, and at the same time a sensitive narrator who takes us from the pre-war period through reunification to the present. Again and again he circles around the question of what it means to have a homeland and to break away from it, to set out or to return – and thus strikes at the heart of our time. A special document of life as well as of an entire century, powerfully narrated and touching, impressive in its colorfulness.

A great work of memory and at the same time highly topical.19

Illustration credits

- Book cover © Rowohlt Verlag

- Edgar Reitz’s parental home (1998) © Thomas Hönemann

- Karl Windhäuser in Geschichten aus den Hunsrückdörfern © ERFilm

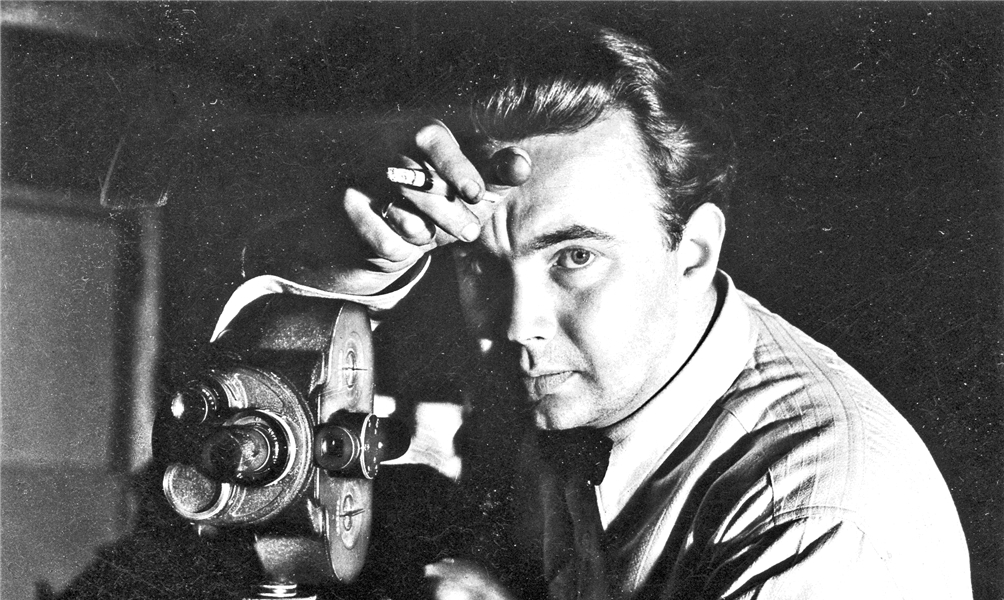

- E. R. during the shooting of Die Reise nach Wien: Taken from a documentary by SWR © SWR

- Portrait Willy Zielke: Collection Dieter Hinrichs

- Working photo Deutschland im Herbst (Germany in autumn) © Studiocanal

- Scene from Die Nacht der Regisseure (The Night of the Filmmakers) © ERFilm

- In 800 mal einsam he says: “There are artists who are great self-promoters. I’m not one of them. For me, the work always comes first.” [↩]

- p. 20 [↩]

- The excerpt can be seen in the exhibition of Café HEIMAT in Morbach. [↩]

- p. 102 [↩]

- The grandparents’ house in Hundheim with the forge, trips to the picnic on the Baldenau by car, visiting relatives in Bochum, cinema showings in the garage, group photos in front of the front door, his father’s record camera, a marriage proposal under the grandfather clock, worries about new blood in the forge, a peaceful death in a nap, evening prayers with the 14 little angels, a downed British bomber in the field outside the village, Zarah Leander’s songs, Lotti and her flirtation with the American soldiers, the philosophers’ sports lesson, visits to Lotti’s and Klärchen’s bedside, the first great secret love (11 years older), the break with the parental home, the names of his relatives, which reappear in the films, usually put together in a different way, or the honor of a Knight’s Cross winner, the oral maturity examination in religion and Margotchen with the fused foot … [↩]

- Also the saying of the grandmother “he looks into the other world. Watch out that he doesn’t die early” (p. 29) and “now I’m six years old and I already have to die” (p. 32, with simultaneous infestation with diphtheria and whooping cough) are original quotes from the life of Edgar Reitz. [↩]

- p. 85 [↩]

- p. 96 [↩]

- The letter that Hermann reads in the car in front of the Boppard train station portal after finally saying goodbye to Klärchen is also “a literal quotation from my life.” (p. 91) [↩]

- Beat Presser: Aufbruch ins Jetzt. Der Neue Deutsche Film im Gespräch, Leipzig (Zweitausendeins) 2021, p. 246 [↩]

- p. 475 [↩]

- Handelsblatt reports on the studies of author and documentary filmmaker Nina Gladitz in 2021; an arte documentary from 2020 also provides information. The Munich City Museum has dedicated a retrospective to Zielke in 2021. His film Das Stahltier (1934) can be seen on youtube and gives a good impression of his influence on Edgar Reitz. [↩]

- p. 163 [↩]

- p. 503 [↩]

- p. 480 [↩]

- p. 297 [↩]

- He writes of the “end of modernity” and likewise of the “television twilight” and the end of cinema. [↩]

- p. 515 [↩]

- https://www.rowohlt.de/buch/edgar-reitz-filmzeit-lebenszeit-9783737101592 [↩]